Disclaimer: machine translated by DeepL which may contain errors.

The Rigakubu News

The Rigakubu News May 2025

Advancing Science >

~ Message from a graduate student~.

Baton to the Next Generation Connected by Tiger Sharks

| Department of Biological Sciences 1st Year Doctoral Student |

| Place of birth Tokyo, Japan |

| Faculty Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, The University of Tokyo |

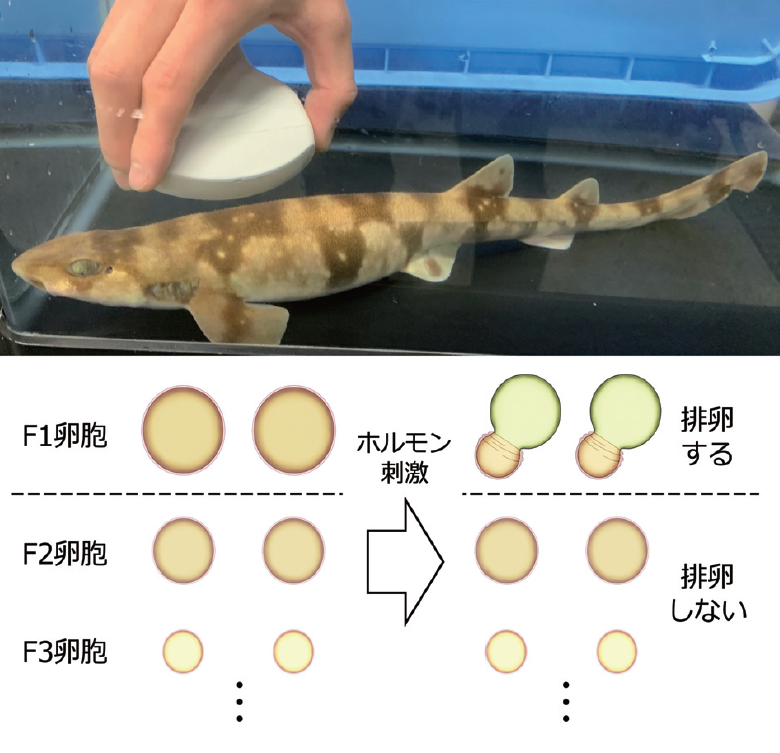

What do you think of sharks when you are asked what kind of creature they are? Many people might answer, "A large and dangerous fish. However, sharks have a number of interesting characteristics as living organisms. Some cartilaginous fishes, including sharks, lay eggs (oviparous), while others, like us, give birth to offspring (embryonic). Some species have placentas, while others cannibalize each other's fetuses. In addition, unlike "ordinary fish*" such as killifish, all species mate. In addition, unlike "normal fish*" such as killifish, all species mate, and some of them are able to reproduce repeatedly by sperm storage, after which the female reproduces alone. Despite their uniqueness, however, cartilaginous fishes have not been studied extensively, especially in terms of reproduction. This is not only because they are large and difficult to handle as experimental material, but also because many species are difficult to breed even in aquariums. In my laboratory, we perform "echography" on tiger sharks, which can reproduce in captivity, to check their reproductive cycle daily without harming the sharks (Figure above).

There have been a number of difficulties in my research to date, but the most difficult was "getting the follicles to ovulate in culture. First of all, we thought it was important to be able to cause and observe ovulation in culture, i.e., in vitro, which normally occurs inside the female body, and we worked to establish a method for doing so. In the beginning, we were not successful in changing the conditions, and most of the follicles did not ovulate. One day, however, I remembered the importance of "shaking" the follicles from my experience of growing killifish embryos when I was an undergraduate, and I tried culturing tiger shark follicles while shaking them. Surprisingly, the ovulation rate was 100% when the follicles were shaken, whereas with the conventional method the ovulation rate was less than 10%. The real thrill of research is to keep one's antennae open for unexpected ideas, even when they seem unrelated at first glance.

As I continued my research, I made an unexpected discovery. At first, I thought of tiger sharks as "relatively small and easy to handle," but it turned out that tiger sharks themselves have very unique characteristics. Within the ovaries of the tiger shark, there are many different sizes of ovaries, and although these follicles exist simultaneously, there are strict "classes" of these ovaries according to size, and each class has a distinctly different response to hormonal stimulation. Only the two follicles in the most advanced stage of development are ovulated. (Figure, bottom). Why do tiger shark follicles have classes and how are they maintained?

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, research on cartilaginous fishes has made little progress because of the difficulties involved. Perhaps it is my own fault, but I have not yet come to the core of the question. However, if we continue to study tiger sharks, we may be able to understand why there are strict classes of oocysts. Further research may help us understand why cartilaginous fishes have diverse reproductive styles, such as oviparous and viviparous, and may even lead to artificial breeding and genetic manipulation of sharks, something that no one has been able to achieve so far. I cannot resist my ever-growing curiosity. I am convinced that the more this research progresses, the more interesting it will become.

(Above) A tiger shark. Although small among sharks, it is still more than 40 cm in length. The reproductive cycle is checked using an echo (hand-held device). (Bottom) "Class" of tiger shark follicles: F1 follicles (the highest class) are stimulated by hormones to ovulate, while other follicles do not ovulate.

* Here we refer to eukaryotic fishes.