Disclaimer: machine translated by DeepL which may contain errors.

The Rigakubu News

The Rigakubu News January 2025

Advancing Science >

~ Message from a Graduate Student~.

Approaching a Theory Beyond General Relativity through Observations of Gravitational Waves

|

| Daiki Watarai |

| Department of Physics 2nd Year Doctoral Student |

| Birthplace Mie Prefecture |

| High School Tokai High School (Aichi, Japan) |

| Faculty Kyoto University |

General relativity is an indispensable foundation for the theoretical explanation of many phenomena in the universe. For example, much of our understanding of the universe, such as the expansion of the universe and the formation of large-scale structures in Big Bang cosmology, has been based on this theory. Even more surprisingly, since Einstein proposed it in 1916, no significant experimental or observational breakthroughs have been found. However, general relativity is not a perfect theory. There are still difficulties that remain to be solved in the theory.

One example is the "cosmological term problem," which is introduced to explain the accelerated expansion of the universe. There is still no clear theoretical explanation as to why the cosmological term obtained by observation has the value it does. General relativity also predicts the existence of a space-time singularity where existing physical laws do not hold due to strong gravity. In such extreme situations, quantum effects of gravity, which cannot be treated by general relativity, become important, but the theoretical understanding of these effects is still in its infancy. Against this background, the construction of a "theory of gravity beyond general relativity," including quantum gravity theory, is extremely important for understanding the whole picture of our universe, and is one of the greatest challenges for modern physics.

Black holes are expected to bring a breakthrough in this difficult problem. A black hole is a celestial body whose gravity is so strong that even light cannot escape, making direct observation by electromagnetic waves difficult. However, in the past decade or so, it has become possible to directly observe black holes by capturing the gravitational waves emitted when two black holes merge. Since binary black hole mergers are accompanied by the strongest gravitational field among all observable phenomena, there may be traces of effects beyond general relativity embedded in the observed gravitational waves. I am analyzing such gravitational wave data precisely to find clues to the ultimate theory (D. Watarai et al., Phys. Rev. D. 109, (084058) 2024), and am theoretically investigating which binary black hole with what mass ratio and spin angular momentum would be the best target for verification, with a view to future observations. Theoretical study of the dynamics of binary black hole mergers is underway (D. Watarai, Phys. Rev. D. 110, (124029) 2024).

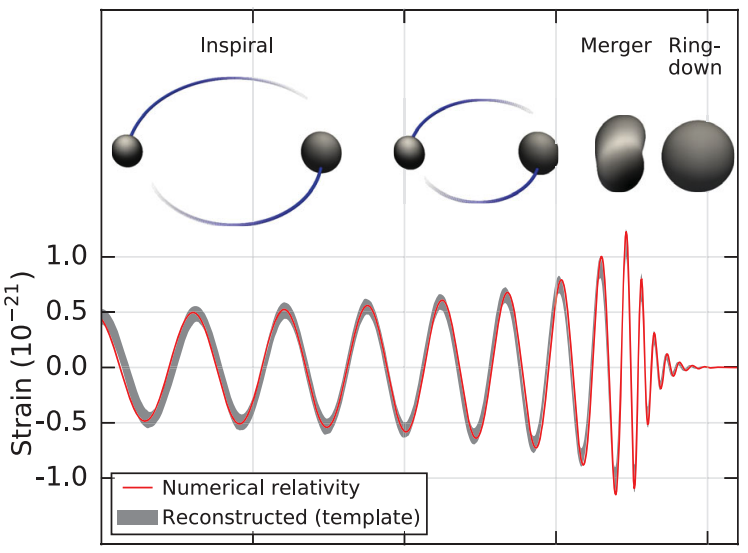

Dynamics of binary black hole mergers and their gravitational waveforms. In general, the merging process consists of an spiral, a merger, and a ringdown, in that order. In the inspiral phase, the two black holes are in nearly circular orbits and the gravitational waveform is periodic. In the merger phase, the two black holes finally merge and the amplitude reaches its maximum value. In the final ring-down phase, the distorted black holes that have merged into one settle into a single stationary black hole. Correspondingly, the gravitational waveform becomes a decaying oscillation (B.P. Abbott et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 061102 (2024)).

I first studied general relativity in my fourth year as a Faculty member and was fascinated by it, even though I struggled with its intractability. I was particularly interested in the fact that the evolution of the universe, which is the largest "existence" we can recognize, can be traced by considering it as a physical object of space-time, and that mysterious celestial objects such as black holes, which defy intuition, can be derived through proper calculations. I had always wanted to be involved in research on the universe, and I decided to do research involving general relativity.

Since entering graduate school, I have been enjoying my research life, following my interests, and I feel that the key to this is to "try your hand at first" and "ask questions when you don't understand something. This may sound obvious, but being aware of these things will lead to new research in unexpected ways. In fact, my life in graduate school has been a continuation of this process. For example, I could never have imagined last year the research I am currently engaged in or the encounters with colleagues with whom I am doing research. These unexpected encounters and discoveries are what make my days more fulfilling and enjoyable than anything else.