Kubo did her undergraduate studies in anthropology at the Department of Biological Sciences at the Faculty of Science, completed her master's degree at the Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, and earned her doctorate from the Graduate School of Science at the University of Tokyo. These first-hand experiences taught her to appreciate the differences between the agricultural and natural sciences. Ultimately, she chose the latter. After balancing family and post-doctoral life at the University Museum, the University of Tokyo, she joined the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences. While continuing her research, she gave birth to a third child and became even more determined to build a career as a researcher. Kubo has come this far valuing her curiosity and connection with the people around her. This is the journey of the School of Science graduate, Professor Mugino Kubo.

Entering the anthropology course at the Faculty of Science after specializing in science at the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Tokyo

I always loved biology and had decided long before entering the university that I wanted to become a biological researcher. At the time of university admissions, I was leaning towards the botany course in the Department of Biological Sciences at the Faculty of Science, but a class taught by Professor Shuichi Hasegawa at the College of Arts and Sciences at the Komaba campus got me interested in the study of animals and evolution.

I thought a lot about what I wanted to study. My desire to do biology on a macro scale led me to the anthropology course at the Department of Biological Sciences at the Faculty of Science. I was attracted to the anthropology course because of the variety of hands-on training, such as anatomy, histology, wild animal observation, and archaeological site excavation. So, I made it my first choice. The anthropology course’s multifaceted approach to research familiarized me with a range of different research methods which later proved to be incredibly useful.

Choosing a master’s program: Graduate School of Agriculture and Life Sciences vs Graduate School of Science

I went into the agricultural sciences because I wanted to do wildlife research. I loved both animals and plants and the relationship between the two intrigued me. I entered the laboratory of Professor Seiki Takatsuki, a wildlife ecology professor who was studying the relationship between Japanese sika deer and plants. He held concurrent positions at the Graduate School of Agriculture and Life Sciences and The University Museum. He collected many skulls of exterminated deer and was planning to conduct morphological research. I had studied basic osteometry in my anthropology course and was interested in the relationship between bones and ecology. So, I began research using deer specimens.

We started by collecting deer specimens with the help of hunters from all over Japan. Japan is long and narrow from north to south, so the habitat for deer differs depending on the region. Professor Takatsuki's ecological research had shown that the diet of the deer living in the northern part of the country consisted mainly of grasses, while the diet of the deer living in the south consisted mainly of the leaves of woody plants. We wanted to see if this dietary difference would influence their bones and teeth.

We were particularly interested in tooth size because eating food wears teeth down. A comparative study of African ungulates showed that if the rate of tooth wear was fast enough, evolution occurred to increase the size of the teeth, especially in height, as a response. In the case of Japanese deer, it would be expected that populations living in the north that are eating more tough grasses would have larger and higher teeth. My graduate school research showed exactly that. I found it fascinating that large-scale interspecies evolutionary phenomena were occurring within a single species of deer.

Heading back to the School of Science for her doctorate

While doing my research, I was becoming keenly aware of the differences between the agricultural and natural sciences. The agricultural science approach is a pragmatic science “for something.” I felt that doing research just for the sake of satisfying one’s curiosity was frowned upon. Being "useful" is important, but my view was that wanting to understand what we do not yet understand is a good enough reason to do science. I had the impression that the Faculty of Science was pursuing such “truth,” so perhaps that is why I felt the gap more strongly.

I took my box of stuff to The University Museum to ask to join the lab of Professor Gen Suwa who had been kind enough to give me guidance throughout my research career. Thus, I returned to study anthropology at the School of Science. The professors who knew me from my undergraduate days called me the "Comeback Kid" (laughs).

Under the supervision of Professor Suwa, I was assigned to work on a project to reconstruct the paleoenvironment and paleoecology from even-toed ungulate and other fossils recovered from early hominid fossil sites. I also continued our deer research as a basic project for trying to extrapolate environmental information from bones.

Elaborating on her doctoral research

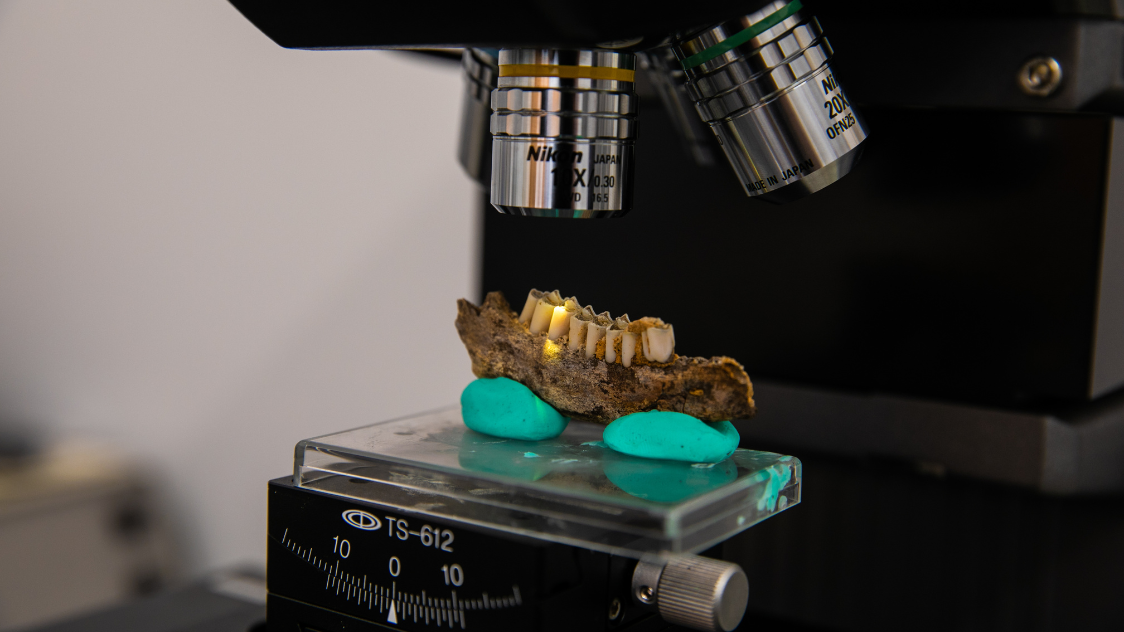

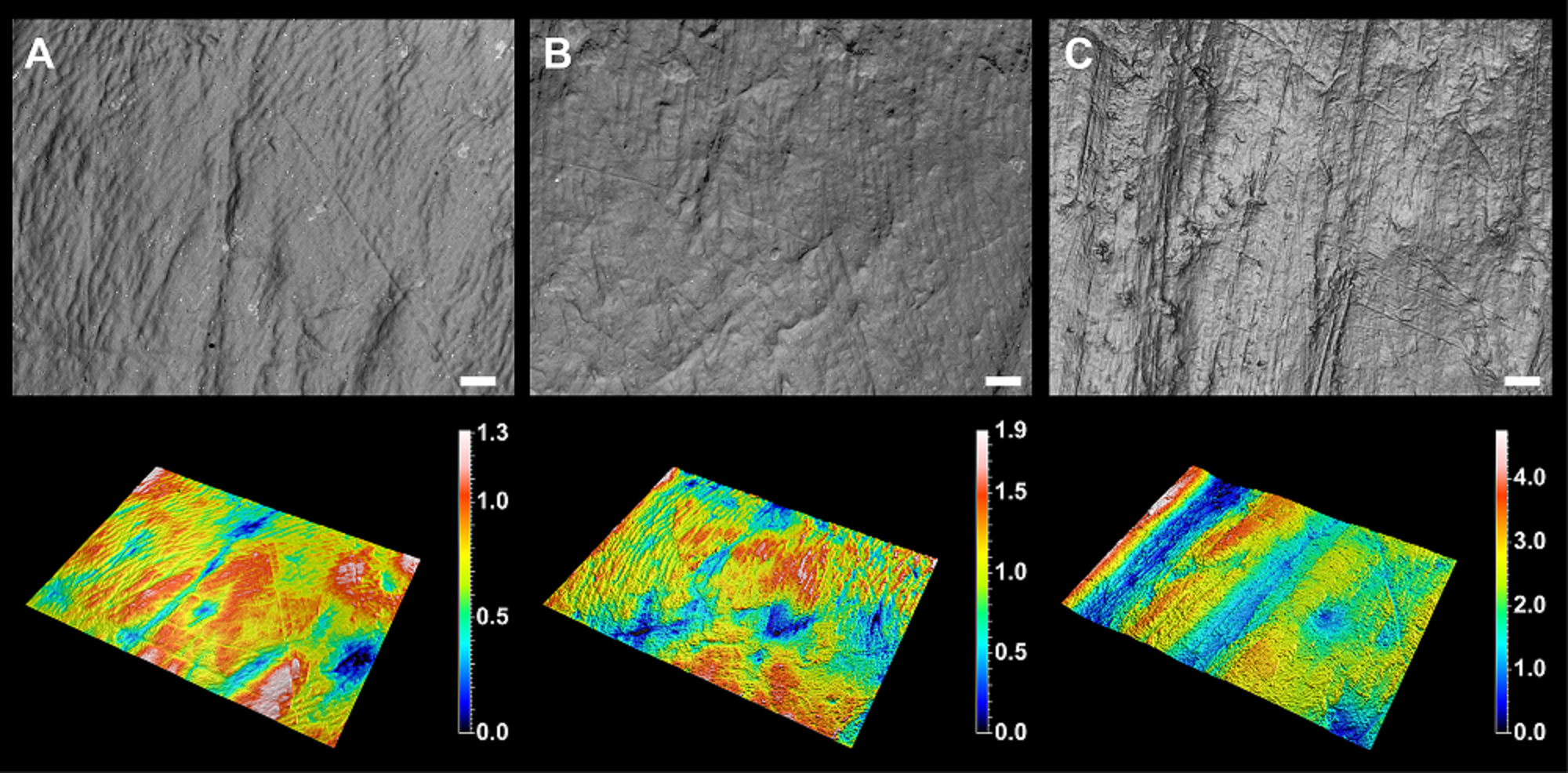

The surface of the teeth has microscopic scars called microwear. The shape of these scars depends on the type of food eaten and it has been studied using electron microscopy since around the 1970s. Our initial aim was to create a basis for reconstructing paleoecology by comparing the microwear textures of deer, whose ecology was well known. We did get some results, but the measurement conditions were influencing the appearance of the scars and we were at a loss to adequately quantify them.

So, I put microwear to the side and started digging deeper into the macroscopic wear of teeth. Since deer diets have regional differences, there must also be a difference in the rate at which their teeth wear down. We compared wear rates of deer teeth and found that the more grass they ate, the faster their teeth wore down. The fact that the rate of tooth wear differs by region means that some groups have functionally long-lasting teeth and others do not. We then created a life table using age-at-death data to calculate the life expectancy of each group and examined the correspondence between this and whether the deer had long-lasting teeth. The results showed that there was a strong positive correlation between the two and that the group whose teeth wore down slowly and lasted longer also had a longer life expectancy. This was summarized in another paper.

Around that time, a project involving Professor Suwa started to investigate cave remains in Okinawa. As a side job, my task was to organize the deer fossil specimens that were being found. These deer were tiny, about the size of a large Shiba Inu (Editor: Japanese dog breed weighing about 20 pounds). This was a typical example of the evolutionary phenomenon called "insular dwarfism," in which large animals become small when they enter an island habitat. In addition, there were no fossils from that period of carnivorous animals from the main island of Okinawa, so the deer in Okinawa must have had no natural predators. I thought this might affect the lifespan of the deer. I calculated the lifespan of the deer by a formula I created based on the height of their teeth, using data from Japanese deer whose ecology was already known. The oldest one turned out to be about 25 years old. Considering that the average life span of deer in the wild is up to about 10 years, these ancient deer seemed to have lived quite a long time despite their small size. Somehow, I managed to get approval for my dissertation, in which I linked the lifespans of ancient and current deer with tooth wear rates. I ended up getting a degree in anthropology by doing deer research.

I was devastated that the research did not lead us closer to reconstructing the paleoenvironment of early humans such as Africa. On the other hand, microwear research did start to flourish a decade later, and mammalian insular dwarfism became central to another project, the research paper of which will be available by the time this article is published.

Moving to the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences after a post-doctoral position at The University Museum

After receiving my degree, I was hired as a post-doctoral fellow at the museum. During this time, I gave birth to my first child, and I was just desperate to publish my doctoral research. I was later selected as a JSPS postdoctoral fellow, and I got deeper into research. However, during that time I had my second child, and it was frustrating that things did not go as smoothly as I would have liked. My husband is also a researcher, and at the time he had a job at the Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum. So, I had to make things work alone.

In the spring of 2015, when I gave birth to my second child, I applied for an open position at the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences and was hired in October. In the Department of Natural Environmental Studies, there are professors from both the agricultural and natural sciences. Perhaps they thought it was interesting that I had experience in both. I got my own office and workspace. It was a fantastic environment which I felt could be the start of many great things.

However… I found out I was pregnant with my third child right after I arrived and got everything set up. I was really torn about what to do (laughs).

First, I asked for advice from my colleague, Associate Professor Maki Suzuki, who I had often talked and had lunch with since I started in my new position. When I told her that I was pregnant and full of anxiety, she said, "What's the problem with that?” The head of the department also congratulated and reassured me. The support and understanding I received helped me feel that I could have a third child and do my best at work.

My husband also left his full-time position to come live with us when I got this job here. Because our second and third child were only a year and three months apart, I thought it would be best to take a proper maternity leave. I was a tenure-track assistant professor, and there was a risk of taking a longer leave considering that I would be reviewed in four and a half years. On the other hand, I also felt that if this was my last chance at maternity leave, I wanted to spend more time with my three children and husband, so I decided to take the plunge and take a year off. I was very glad that I decided to take a longer leave because the postpartum period was very difficult due to an unexpected C-section.

At the Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, she focuses on microwear textures again, an unresolved challenge since her time at Professor Suwa’s lab

I wanted to research tooth wear marks, the project that Professor Suwa had given me. Equipment (confocal microscopes) that could take 3D images of minute surface undulations began to appear around 2004. Scratches on tooth surfaces, which until now had been counted using 2D images, could now be obtained as 3D data. I had firsthand experience with the difficulty of quantifying scratch marks observed under an electron microscope, and I had a feeling that the new method would eventually become mainstream. I managed to purchase a used one at a price that I could afford with my arrival expenses, and I was able to buy it right before I went on maternity leave, as my belly bump was becoming quite enormous.

I returned from maternity leave in 2017 and immediately started using this machine to make measurements on the deer specimens. At first, it was only Japanese deer, but some students expressed interest in the project, so we also took data on Japanese serows, wild boar, and Japanese macaque. We have finally started to get some results.

What the findings revealed

The first step of paleoecological reconstruction based on microwear textures is to accumulate basic data using living wild animals with known diets. This part of the project is progressing smoothly and several papers have been published. In my research on deer, I was able to quantitatively show that northern deer, which eat a lot of grass, have more and deeper microwear scars on their teeth. It felt like I finally handed in the homework assigned ten years ago.

My husband is a dinosaur researcher, and we are collaborating on a study to infer dinosaur diets from microwear textures. Such research was started in anthropology, then European and other laboratories applied it to mammals. However, dinosaur research was virtually untouched, so we saw potential there. Furthermore, an excellent German postdoc who was interested in dinosaur microwear research came to my lab as a JSPS invitational foreign research fellow. With the dinosaur microwear research system in place, an international collaboration of feeding experiments on present-day crocodiles as a comparison subject proceeded, and we published a paper. Two dinosaur microwear papers were also published in 2022, with another one forthcoming. All of the dinosaur research has been published with press releases because of their high impact. I believe we are spearheading research on dinosaur microwear textures.

Advice for students who are interested in science

The reason why I am glad that I chose the natural sciences is the attitude that the pursuit of truth itself is the most highly cherished, and that it is the primary force of science. When you find a phenomenon that you find interesting or something that you want to explore more deeply, I think it is okay to put aside the question of whether it will be useful for something or beneficial to someone. If you work at it until you feel that you understand it, scientific progress will naturally follow.

Even research that once failed may be carried out differently as technology advances. Always keep an open mind. If your research project did not go well on the first try, you may be able to succeed the second time around by using a new method, so you push forward. I think it is vital to have this kind of attitude.

When we were releasing a press release about our carnivorous dinosaur microwear paper, the German postdoc said in an interview, "Our research is curiosity-driven.” I was very happy that she felt the same way about what I thought was most important. When you follow your curiosity, sometimes it is difficult to make money, but someday someone will certainly say, "That's fascinating!”

laboratory: https://sites.google.com/edu.k.u-tokyo.ac.jp/mugino-kubo-lab/home

※Year of interview:2023

Interview and text: Naoto Horibe

Photography: Junichi Kaizuka

![リガクル[RIGAKU-RU] Exploring Science](/ja/rigakuru/images/top/title_RIGAKURU.png)